par acaoh | Jan 30, 2013 | CULTURE

Boussad Berrichi est docteur en Lettres de l’université de Paris. Etabli au Canada, il est professeur-chercheur dans le domaine berbère et la littérature comparée. Il est aussi l’auteur de Mouloud Mammeri, Amusnaw et l’éditeur scientifique des deux tomes de Mouloud...

par acaoh | Nov 8, 2012 | ÉVÉNEMENTS

Les amis de l’école de tamazight INAS sont heureux de vous inviter, en famille, au COUSCOUS-BÉNÉFICE, qui aura lieu samedi 24 novembre, à 19h00, au Centre Lajeunesse, sis au 7378 rue Lajeunesse, Montréal (métro Jean-Talon). À cette occasion, ils vous ont concocté un...

par acaoh | Août 24, 2012 | Enseignement, ÉVÉNEMENTS

Chers membres de note communauté, Le comité des parents d’élèves de l’école de Tamazight a Ottawa-Gatineau voudrait organiser un BBQ pique-nique bénéfice. Les profits de ce pique-nique seront utilises pour financer les sorties et autres activités pour les élèves de...

par acaoh | Mai 26, 2011 | Enseignement

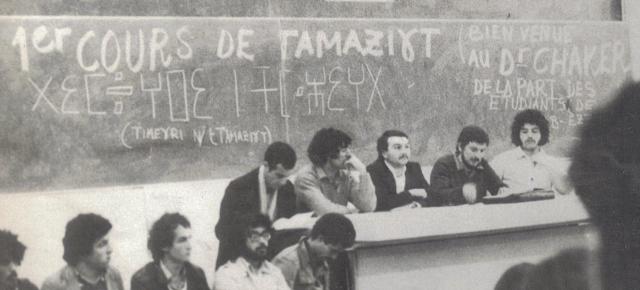

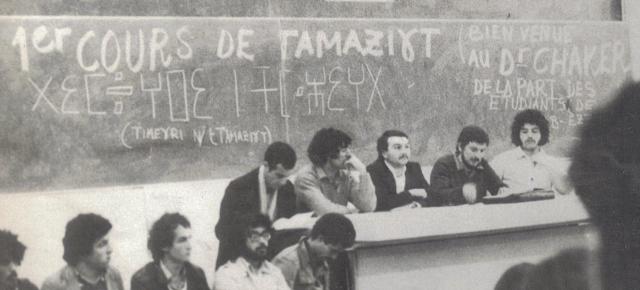

I. The Tamazight language and the Amazigh people Tamazight or Amazigh language1, also referred to as Berber in western literature, is the language spoken by Amazigh people, the indigenous of Tamazgha (North Africa plus Mali, Niger and the Canary Islands). Before the...

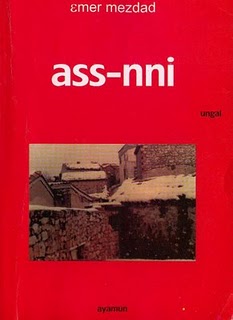

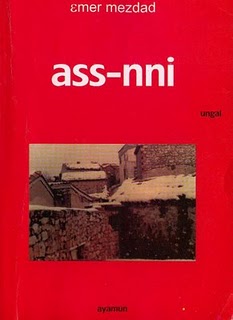

par acaoh | Mai 26, 2011 | CULTURE, Idlisen, Litterature

Ass-nni est le titre du nouveau roman de Amar Mezdad, venu achalander un peu plus la petite bibliothèque berbère. La trame se situe dans les années 90 à cette époque charnière de notre histoire récente qui a vu le pays avorter de l’espérance démocratique et accoucher...